Hiring a ghostwriter of the calibre of J.R. Moehringer, on George Clooney’s recommendation, is one of the few wise moves Prince Harry has taken in the last five tumultuous years. Spare is compelling because it captures Harry’s unresolved emotional suffering, his panicked, blinkered determination, his improbably winning rapscallion voice, and his distorted, confused worldview. This hyper-personal narrative is an unexpected literary success because Moehringer is able to hone in on the crucial facts hidden behind jumbled recollections.

After a Sandringham shoot, the monarch and her grandson confront each other as she tries to flee in her Range Rover, a scene that will live in infamy for generations. Harry stammers, “I was told that, er, that I have to ask your permission to propose [to Meghan]. Her Majesty responds, “Well then, I suppose I have to say yes.” It’s great fun to see Harry’s mind work overtime trying to figure out her response to the central question of this memoir. “Was she being sarcastic? Ironic? Was she indulging in a bit of wordplay?” Inconceivable to any sane reader, the queen’s words must have left that ruddy visage in a knot of confusion.

Diana, by far the story’s most influential character, is only glimpsed briefly but brilliantly. The inconsolable grief of 12-year-old Harry’s loss provides Moehringer with a dramatic, overarching literary device. Harry came to the terrible conclusion that his mother was actually still alive. She had discovered a means to “disappear,” to leave behind her troubled past and make a “new start” (perhaps in Paris or a log cabin in the Alps). He can’t shed a tear for her save for the one at her burial at Althorp, where the thought of her return has frozen his heart. Harry’s memories are locked away from even himself by the clamour of the world’s grieving and the unending tawdry excavations of what really happened that night in the Pont de l’Alma tunnel, until he had a breakthrough in his mid-30s in a therapist’s office. He remembers only one thing about his mother’s death: the press and the paps, who he calls ghouls, pustules, dogs, weasels, idiots, and sadists, and who he says “tortured” his mother before “coming for me.” The anger that he feels towards them is like a “red mist” that never dissipates. Every step of the way, the reader is right there with him as the hack-pack makes fun of the clueless prince for his immature mistakes.

To Harry’s surprise, his magical thinking about Diana’s “disappearance” permeates many other areas of his life. As he says, it’s as if he’s the first white male to realise that primogeniture (or the “hierarchy,” as he calls it with malicious emphasis) is wrong. In other words, of course. It was conceived under the monarchy. Many of his classmates and teachers lived in grand homes across England, but he and his younger siblings were left to make do with a musty manor and a menial job at a bank (if lucky). We can all agree that Harry has succeeded more than most people. He was only 30 when he became heir to Diana’s fortune and the Queen Mother’s after she passed away in 2002. (He tells us that “vacuum packed meals brought by Pa’s chef” frequently stock the refrigerator at his modest bachelor pad in the hardly shabby surrounds of Kensington Palace, which he calls “Nott Cott” for short.)

Harry’s difficulty is not so much his position in the birth order as it is the century he was born in and now lives in. William reportedly instructed Harry that he should cut off his “flaming, efflorescent beard,” which is a reference to the Red Earl Spencer, Queen Victoria’s erratic Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. His descendant, Prince Harry of Wales, is a classic pistol-whipping 19th-century aristo always spoiling for a fight, whether it’s mowdowning the enemy in Afghanistan, yomping through Wales with trench foot, or trekking the North Pole with a frost-bitten penis that he later cocoons in a “bespoke cock cushion” (an apt description, perhaps, of his Goop-like existence in Montecito). His army helicopter instructor informs him, “You’re not too concerned, if I may say so, Lieutenant Wales, with dying.” As I put it, “I explained that I hadn’t been terrified of death since I was 12 years old.”

The Megxit disaster puts Harry in a bind and forces him to take stock of his situation more honestly than at any other time in the novel. He thinks, “after decades of being brutally and methodically infantilised, I was now unexpectedly abandoned and insulted for being immature” when holed up with Meghan and Archie in a fortified Los Angeles crib provided by writer-director Tyler Perry. More irony can be found. Although Spare constantly complains about how much control his father and brother have over his life, the reality is that their influence is far more limited than he believes. Charles does not pause when he answers, “It’s all decided by the government,” but he does order his “darling lad” to put all recommendations for a hybrid royal position in writing. Four months before his father’s coronation, Harry makes his family feel ashamed, which is the worst thing he does to them. When the Palace’s curtains are pulled back, it turns out to be a run-down movie studio where contract actors compete for the most important roles and good reviews by keeping track of their own public appearances in the court periodical. According to Harry, most arguments in his family revolve around who will receive the most favourable media attention. Kate is cautioned from picking up a tennis racquet while at a gym should the attractiveness of the photo steal the spotlight from Prince Charles. Constant leaks, plants in the background, and sneaky small talk by assistants are all ways to help one principal while hurting the interests of another.

The institution’s betrayal of Harry and Meghan is the burning point at the centre of his rage. One gets the impression, however, that he is also deeply embarrassed by his marriage, which may be another source of his fury. The promise Harry made to his bride was the pinnacle of his magical thinking. His enthusiasm and relief at having discovered his “perfect, perfect perfect” partner led him to encourage her dream that they would one day rule the globe as humanitarian celebrities, riding on the combined might of her Hollywood glitz and his royal status. How could he tell her, from his comfortable perch on the Ikea sofa in Nott Cott, that he was a relative pauper in the larger scheme of the monarchy? One can’t help but sense that he seeks an apology for the fact that his lofty goals exposed his own inadequacies.

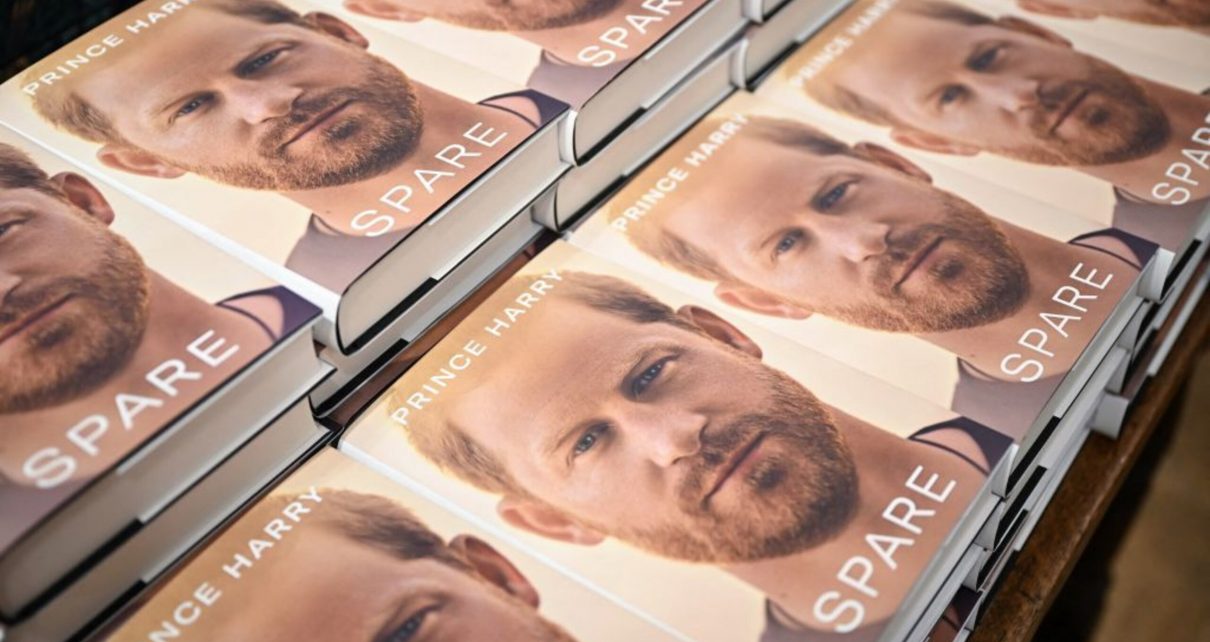

- Curated from original content in The Guardian. Spare can be purchased at Amazon and delivered to your address in Nigeria. Click here to get a copy.