Britain solidified a new pact with Rwanda, aiming to circumvent a court ruling impeding its asylum deportation initiative, marking a significant setback to the country’s immigration strategy. The plan to transfer asylum seekers to Rwanda encountered a legal obstacle, emphasising a critical blow to the government’s policy.

The scheme involving Rwanda remains pivotal in the government’s efforts to curb illegal migration and is closely monitored by nations contemplating analogous measures. However, the United Kingdom’s Supreme Court ruled the plan incompatible with international human rights laws entrenched in domestic regulations.

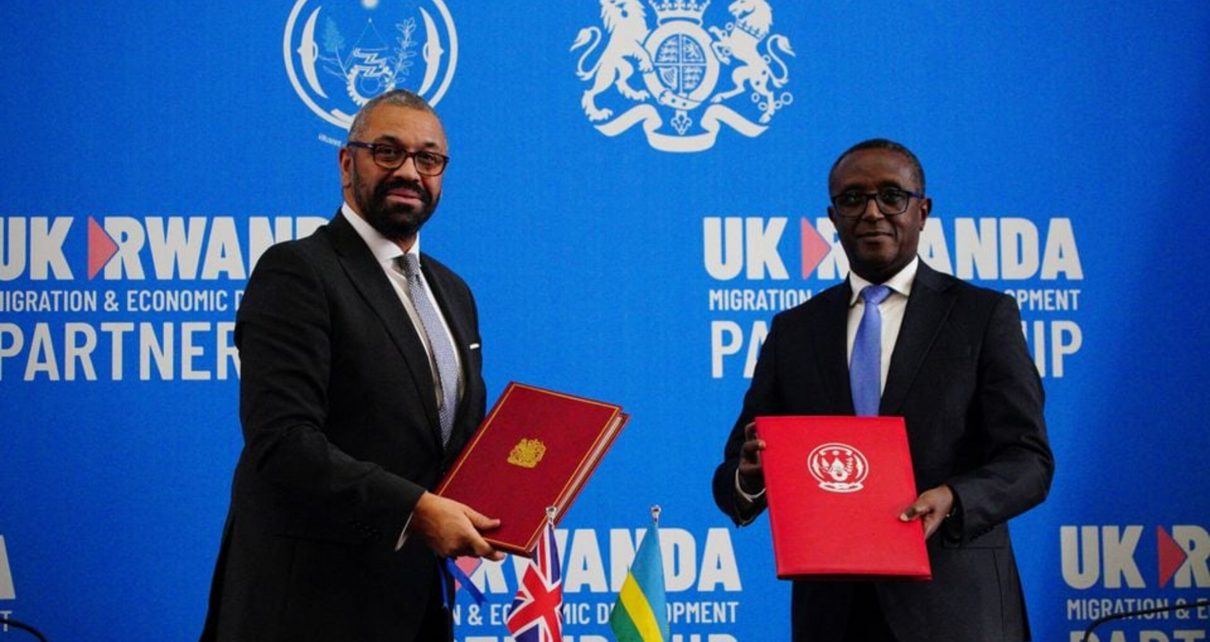

British Home Secretary James Cleverly, alongside Rwandan Minister of Foreign Affairs Vincent Biruta, inked the treaty in Rwanda’s capital, Kigali. This treaty, replacing a non-binding memorandum, assures that Rwanda won’t expel asylum seekers to life-threatening conditions, a paramount concern of the court.

“I really hope that we can now move quickly,” Cleverly expressed to reporters in Kigali, optimistic about the imminent transfer of migrants to Rwanda, addressing the court’s apprehensions.

Nevertheless, legal experts and charities remain sceptical about the immediate commencement of deportation flights, especially with an impending election on the horizon. The opposition Labour Party, leading in polls, pledges to discard the Rwanda policy if elected.

The contentious policy aims to redirect thousands of asylum seekers arriving on British shores to Rwanda, deterring perilous crossings over the Channel from Europe in unsafe boats.

The pact includes substantial financial backing, with an initial payment of £140 million ($180 million) to Rwanda, promising further funds to sustain the care and lodging of the relocated individuals.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak faces mounting pressure to reduce net migration, one of his administration’s top priorities. The Supreme Court’s rejection of the Rwanda plan, introduced by former Prime Minister Boris Johnson, highlighted the potential risk faced by deported refugees and triggered the development of new legislation designating Rwanda as a “safe country.”

However, legal challenges and political disputes loom over this decision. Immigration lawyer Sarah Gogan deemed the policy unrealistic, highlighting Rwanda’s human rights concerns and predicting legal confrontations. Labour’s Yvette Cooper dismissed the government’s efforts as another futile attempt, labelling them as mere “gimmicks.”