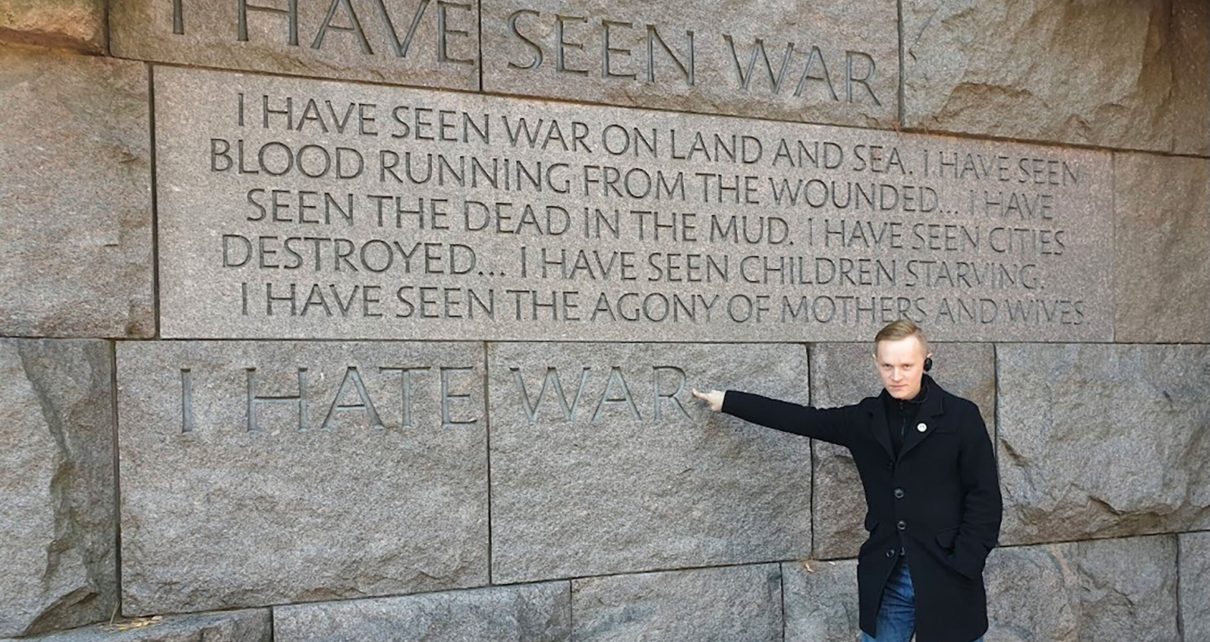

In picture above: Vladimir Zylinski is an election observer for voting rights movement Golos. He and Golos are on the register of “foreign agents.” Handout via REUTERS

Since late 2020, Russia has added dozens of Kremlin critics to its register of “foreign agents.” Reuters contacted them to find out how the designation has changed their lives.

By Lena Masri

Long before Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine and the mass detentions of Russian peace protesters, the Kremlin was already stifling dissent – with choking bureaucracy.

Throughout 2021, the Kremlin tightened the screws on its opponents – including supporters of jailed opposition leader Alexei Navalny – using a combination of arrests, internet censorship and blacklists. The crackdown accelerated after Russia invaded Ukraine. Now a Reuters data analysis and interviews with dozens of people chart these tactics’ success in eroding civil freedoms.

A widely used weapon in the Kremlin’s armoury is the state’s register of “foreign agents.” People whose names appear on this official list are closely monitored by the authorities. Among them is Galina Arapova, a lawyer who heads the non-profit Mass Media Defence Centre, which advocates for freedom of expression and is based in Voronezh, western Russia.

The Ministry of Justice declared Arapova, 49, a “foreign agent” on Oct. 8. She wasn’t told why. The ministry didn’t comment for this article.

The designation brings close government scrutiny of Arapova’s daily life and a mountain of red tape. She must file a quarterly report to the Ministry of Justice detailing her income and expenses, including trips to the supermarket. The report runs to 44 pages. Reuters reviewed one such report.

Every six months, “foreign agents” must file an account to the ministry of how they spend their time. Some retired people list their household chores. Arapova states in her account simply that she works as a lawyer, unsure whether she’s providing enough detail.

She offers legal advice to other “foreign agents,” but says she’s often in the dark about what the rules require. “We don’t fully understand what exactly they want us to do because the law is very vague,” she told Reuters. “They don’t explain anything. Do we have to list all utility costs and receipts from supermarkets or just overall expenses for three months?”

She prints out then mails the report to the ministry, the pages carefully stapled together. If a page is missing or the report arrives late, she could be fined. Repeated violations can lead to prosecution and up to two years in jail.

Reuters sent detailed questions to the Kremlin, the Ministry of Justice and other Russian agencies about the rules imposed on “foreign agents.” None provided any comment.

The bureaucracy doesn’t end there.

People deemed to be “foreign agents” must set up a legal entity, such as a Limited Liability Company. This too is added to the list of “foreign agents” and must report its activities to the authorities. The process involves finding premises to register a legal entity, drawing up seals and electronic signatures, submitting documents to the tax service, and opening a company bank account. The company has to undergo annual audits but, as Arapova explains, auditors are not keen on taking clients with “foreign agent” status, and those who do tend to charge a lot.

She estimates that complying with the requirements so far has cost her about 1,000 euros. Accounting fees will add to that sum when her LLC undergoes an audit. Even more costly is the endless time spent on meeting the requirements.

“It takes time away from my work and causes a lot of psychological stress,” she said. “When you’re forced to do this type of bureaucratic and humiliating nonsense it’s a kind of psychological torture.”

And that, some analysts say, is the Kremlin’s aim. These registers, said Ben Noble, associate professor of Russian politics at University College London, are “part of a broader project, which involves both moving against individuals who are publicly critical of the government and also trying to have a broader chilling effect to stop people from even thinking about getting involved with opposition or critical, independent journalism in the first place, for fear that they will, essentially, be framed by the authorities as traitors.”

Reuters contacted all 76 people on the list of “foreign agents,” which is compiled by the Ministry of Justice and published on its website. Sixty-five responded to a series of questions about how the designation affected them, creating a unique dataset. These people include journalists, pensioners, activists and performers. All are Kremlin critics.

The respondents, all Russian citizens, denied working for a foreign power. Most said they had received no explanation for their inclusion on the list. Several lost work or were forced to change jobs. Others said they left Russia because they didn’t feel safe. Dozens said they reduced their social media activity because everything they publish, even personal social media posts, must contain a 24-word disclaimer that identifies them as a “foreign agent.” Since the invasion of Ukraine, at least five people on the register said they have been briefly detained for involvement in anti-war protests or while carrying out reporting related to the war. At least one further detention was reported locally.

Many critics accuse Putin of bringing back Soviet-era style repression. The Kremlin says it is enforcing laws to thwart extremism and shield the country from what it describes as malign foreign influence. When it comes to Ukraine, Putin says he is carrying out a “special operation” that is not designed to occupy territory but to destroy its southern neighbour’s military capabilities, “denazify” it and prevent genocide against Russian-speakers, especially in the east of the country. Ukraine and its Western allies call that a baseless pretext for a war to conquer a country of 44 million people.

Expanding list

The “foreign agents” law was introduced in 2012 and aimed at non-governmental organisations that were politically active and received funding from abroad. Political activity can encompass legal and human rights work and journalism, Arapova said. The law has evolved to cover an ever-expanding number of groups and people. In 2017, Russia’s Justice Ministry started designating media outlets as “foreign agents.” In December 2020, authorities used the designation in a new way – they labelled individuals as “foreign agents” for the first time.

Veronika Katkova, a 66-year-old pensioner who observes elections for voting rights organisation Golos in Russia’s Oryol region, south of Moscow, was added to the list at the end of September 2021. That was shortly after parliamentary elections that the opposition said were stacked in favour of Putin’s United Russia party. Golos alleged there were widespread voting violations, which the Kremlin denied. Katkova believes she was labelled a “foreign agent” because of her involvement with Golos. Russian authorities didn’t respond to questions about the matter.

As a “foreign agent,” she reports all her expenses to the Ministry of Justice every quarter, including for food, medicine and transportation, and every six months she reports her activities, such as cleaning her home and cooking. In January, she forgot to add to a social media post the necessary disclaimer flagging her foreign-agent designation. The state communications regulator opened a case against her, which could lead to a fine, she said. The regulator didn’t comment for this article.

Lyudmila Savitskaya, a freelance journalist from Russia’s Pskov region that borders the Baltic states and one of the first people to be added to the list in December 2020, said the designation left her no privacy. “The state knows everything I do, what my bank accounts and expenses look like, where I go and what medicines I buy.”

Thirty people from the list told Reuters they have left Russia.

Journalist Yulia Lukyanova, 25, is one of them. She now lives in the Georgian capital Tbilisi, where many other dissident Russians are settling. Russians can stay in Georgia, a former Soviet state on Russia’s southern flank, for up to a year without a visa. Some Georgians resent their presence, however, with memories of Russia’s 2008 invasion of the country still fresh. Lukyanova shared a photo of an anti-Russian sticker that she said appeared on her street. It shows a matryoshka doll with sharp teeth. She said a friend had trouble finding a flat because some people don’t want to rent to Russians, even Russians who are critical of Putin. She believes Georgians are afraid that if their country hosts dissident Russians, it might become a Kremlin target. “It must be hard for Georgians and I’m sorry,” she said.

Lukyanova opposes Russia’s war in Ukraine. “I don’t want people to be sent to fight a war they didn’t vote for, to be imprisoned for protesting against it or reporting on it as journalists.”

Elizaveta Surnacheva, 35, a journalist from Moscow, moved to Kyiv in March 2020, then on to Tbilisi and finally Riga. Her Ukrainian husband, who is of fighting age, stayed in Ukraine.

“It’s very frightening,” said Surnacheva. “Even in my worst nightmare, I couldn’t imagine that I would be discussing with my husband which blanket would best protect him from the fragments of the mirror in the bathroom if he took cover there in a blast. My dream now is to get back to a free Ukraine and to help rebuild Kyiv and our life there.”

She continued to add the foreign-agent disclaimer to her social media posts even after leaving Russia because she wanted to be able to go home to visit her parents. But that changed on Feb. 24, when Russian troops entered Ukraine and Putin’s crackdown on his domestic opponents intensified. Now Surnacheva and at least 20 “foreign agents” interviewed by Reuters say they are afraid to return to Russia for fear of arrest or harassment. “I made the decision that I’ll no longer follow any of these ‘foreign agent’ rules,” she said. “It is clear to me that I will not go to Russia in the coming years.”

Treason against the motherland

Others have faced consequences after they were accused by authorities of not following the requirements of the foreign agents law. At least nine people from the list said they have been fined or have had cases opened against them that could result in fines. The financial penalty can run as high as 300,000 roubles ($3,600), according to the legislation.

Vladimir Zylinski, 37, is a programmer who also acts as a regional election observer for the voting rights organisation Golos. On Sept. 14, days before the parliamentary election, he filed a complaint to the electoral commission in the northwestern Pskov region because it was setting up a mobile polling station in a wealthy suburb that is home to many local officials. This went against election rules, he said. Mobile stations are intended for areas with poor transport links, he wrote in his complaint, which was seen by Reuters. “An excellent road” leads to the wealthy suburb, he wrote, “and local residents … have cars.”

Zylinski said authorities subsequently opened a case against him, which could lead to a fine, for omitting the 24-word “foreign agent” disclaimer from his complaint – even though Zylinski wasn’t added to the list of “foreign agents” until Sept. 29, over two weeks later.

Twenty two people were declared “foreign agents” on that date – a record number. Twenty of them were members of Golos. Golos itself, which documented thousands of alleged election violations last year, was labelled a “foreign agent” in August. Russian authorities didn’t respond to Reuters’ questions about the matter.

Zylinski has lived with his family in Tbilisi since the beginning of this year. He no longer worries about the case against him. He says he is more concerned about how the war is impacting Ukrainians and people who have fled Russia. He is helping a woman he knows from Ukraine to collect aid for Ukrainian medics and is volunteering at collection points for aid shipments to Ukraine. He also counsels refugees who have come to Georgia or are on the way there. He says that some in Russia would consider what he is doing “treason against the motherland.”

Like many others, Arapova, the media lawyer, challenged her inclusion on the register of “foreign agents.” At a court hearing in February, she learned that one of the reasons for her designation was that she received foreign funding – a $400 payment for speaking at a media conference in Moldova about European data protection.

She believes that she has been classified as a “foreign agent” because of her work promoting free speech and in defending journalists whose output is critical of the Russian government.

Lukyanova, the journalist, received a similar explanation at her appeal. She used to work for Proekt, a Russian investigative news outlet, whose publisher Project Media was registered in the United States. That meant she received a foreign salary.

In 2021, the Ministry of Justice declared Project Media an “undesirable” organisation, effectively forcing it to end its operations in Russia. The register of “undesirable” organisations started with four names in 2015; it now contains 53. People who work for “undesirable” organisations, donate to them or share their material on social media risk prosecution. It becomes practically impossible for these organisations to function. Since the invasion of Ukraine, the ministry has added three names to the register: a Ukraine-registered movement that advocates for the rights of people from Russia’s Volga region and two investigative media outlets.

People who challenged their inclusion on the list of “foreign agents” were given other reasons too, such as republishing content by other “foreign agents” and transferring money from foreign bank accounts to their Russian accounts.

So far, no one has managed to get their name removed from the register.

“Terrorists and Extremists”

In the early morning of Feb. 15, 2019, armed police and intelligence agents burst into Timofey Zhukov’s home in Surgut, an oil town in western Siberia. They knocked him to the floor, then began searching his belongings, he said. It was one of at least 20 raids across Surgut that day, Zhukov told Reuters. He said all of those targeted were Jehovah’s Witnesses, an organisation that had been banned in Russia two years earlier after Russia’s Supreme Court ruled it extremist. Russian authorities argued the organisation promotes its beliefs as superior to other faiths.

Zhukov and his fellow believers were detained for questioning and accused of “continuing the activities of an extremist organisation,” a crime that could lead to imprisonment. Russian authorities didn’t respond to questions from Reuters about the matter.

Zhukov, who trained as a lawyer, told Reuters he and the others have done nothing unlawful. The Surgut branch of the Jehovah’s Witnesses was liquidated after the ban came into force, Zhukov said, “but we continue to believe, regardless of whether there is a legal entity.”

Jarrod Lopes, a spokesperson for Jehovah’s Witnesses, told Reuters, “If Russia’s skewed view of extremism was imposed on everyone, then just about every believer and non-believer would be banned in Russia, not just Jehovah’s Witnesses.”

Jehovah’s Witnesses say they are politically neutral. They don’t lobby or vote for political candidates or run for office. They don’t sing national anthems or salute the flag of any nation because they view it as an act of worship. They also reject military service – a choice that has led to the imprisonment of Jehovah’s Witnesses members in several countries.

Religious life in Russia is dominated by the Orthodox Church, which is championed by President Vladimir Putin. Some Orthodox scholars view Jehovah’s Witnesses as a “totalitarian sect.”

Zhukov’s case is still working its way through the courts. But his name already appears on the register of “terrorists and extremists” and he can’t travel outside the city without permission. He has only restricted access to his bank account. If he wants to withdraw more than 10,000 roubles ($120) in a single month he has to explain the reasons: “I need to pay for the apartment, for kindergarten, for school.”

Over the past three years, Zhukov said, police and investigators threatened him with jail and he was forcibly admitted to a hospital in Yekaterinburg, 1,000 km away, to undergo a psychiatric examination. He said he spent 14 days there alongside patients who included violent criminals. “I passed all the tests, some involving devices on my head.”

The list of “terrorists and extremists” has grown steadily. At the end of 2021, there were more than 12,200 individuals and groups on the register, up 13% from about a year earlier. Russia doesn’t publish the dates on which names are added, but Reuters compared the current list with previous versions saved on archive.org, which stores web pages.

Violent extremists such as neo-Nazi groups and Islamic State appear on the list. At least 400 local Jehovah’s Witnesses groups are currently designated as extremist or terrorist, according to a Reuters analysis of the Russian list.

In January, a 56-year-old female Jehovah’s Witness was sentenced to six years in a penal colony for extremism. The following month, a 64-year-old man was handed a six-year sentence on the same charge. Both had insisted their innocence. Zhukov too insists that his religious beliefs do not contravene any law.

“As a lawyer, I can very easily distinguish between a religious association and a legal entity,” he said. “I can’t explain why some lawyers and judges can’t see the difference. And what threat do we pose?”

“We preach, we tell people about the kingdom of God from the Bible.”

Internet crackdown

On the day Russian troops poured into Ukraine, Russia’s state communications regulator Roskomnadzor put out a statement, demanding that media outlets only use official Russian sources to cover the “special operation” in Ukraine. Otherwise they could be blocked and face a fine of up to 5 million roubles.

Russian authorities, which did not comment for this article, have since doubled down on censorship in Russia. On March 4, lawmakers passed amendments that criminalised “discrediting” Russian armed forces or calling for sanctions against Russia. Lawmakers made the spread of “fake” information an offence punishable with fines or a jail term of up to 15 years, a move that led some international news outlets to halt reporting in Russia.

Authorities also restricted access to Facebook and Twitter and blocked several independent media and Ukrainian websites.

In response, Twitter said people should have free and open access to the internet, particularly during times of crisis. Nick Clegg, president of global affairs for Facebook’s parent company Meta, said millions of ordinary Russians would be cut off from reliable information.

Several Russian media outlets suspended their work. Ekho Moskvy, a liberal radio station, was dissolved by its board after the prosecutor general’s office blocked its website over its coverage of the war. Television channel Rain suspended its work after its website was blocked. The Novaya Gazeta newspaper, whose editor Dmitry Muratov was a co-winner of last year’s Nobel Peace Prize, said it would pause its work until the end of Russia’s “special operation” in Ukraine.

Online censorship was already rising before the invasion. Ahead of the September elections last year, major internet outages were caused by a crackdown on websites linked to jailed opposition leader Alexei Navalny and on technology used to circumvent online bans.

Around 200,000 websites were blocked in 2021, according to data from Roskomsvoboda, a group that monitors internet freedom in Russia. They included the website of OVD-Info, which has documented anti-Kremlin protests for years. This year, as of March 10, more than 46,000 sites have been blocked, according to Roskomsvoboda.

A REUTERS SPECIAL REPORT