For eight years Nigerian housewife Mallama Baraka suffered in silence as the eye disease trachoma, which can blind but is entirely preventable, slowly took its toll.

It started with a watery discharge and a burning, itchy sensation in her eyes. Her eyelids swelled and her eyelashes turned inside them, causing her extreme pain each time she blinked. Over time, she began to see less clearly.

“It became hard for me to do my daily chores … but the clinic is far and it would take time and money to go there. I thought whatever is in my eyes will go away if I keep washing them,” Baraka said by phone from Bali town in eastern Nigeria.

“It was only when the health workers came to my home in 2019 and told me about my condition that I realised I could have gone blind if I had not had the surgery,” said the 43-year-old mother of three, whose family grows beans and maize for a living.

Caused by bacteria and spread through direct and indirect contact, and by flies that come in contact with the eyes or nose of an infected person, trachoma is the leading infectious cause of blindness in the world.

It is responsible for the blindness or visual impairment of about 1.9 million people, says the World Health Organization (WHO), and about 137 million more people living in 44 countries remain at risk of trachoma blindness.

While countries including Nigeria have managed to reduce trachoma over the years, health experts warn that disruptions caused by the coronavirus pandemic could jeopardise efforts to eliminate it.

The WHO said in September the outbreak had hit programmes tackling Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) such as trachoma, with countries having to suspend mass treatment interventions and active-case finding and delay diagnosis and treatment.

Critical personnel have been reassigned to deal with COVID-19 and the manufacture, shipment and delivery of medicines has been disrupted, it said, warning of “an increased burden of NTDs”.

Joy Shu’iabu, director of programs for the charity Sightsavers in Nigeria, said the pandemic had been a challenge, with all NTD activities initially suspended during the country’s lockdown.

“We had to make sure that we followed all the guidelines and that our staff and communities were safe before we could start services again,” she said. “We are now building up gradually … I would say our activities are running at 60% pre-COVID levels.”

DISEASE OF THE POOR

On Saturday, the WHO will mark World NTD Day after launching a roadmap setting out global targets to tackle 20 of the diseases including trachoma by 2030.

Together, these curable or preventable diseases affect more than 1.7 billion people in some of the world’s poorest countries, often severely disabling them and leaving them isolated and unable to earn a living.

Trachoma, which is often described as a disease of the poor, is found in crowded areas where clean water and sanitation are scarce and is hyperendemic in parts of Africa, Central and South America, Asia, Australia and the Middle East.

Spread from person to person through unwashed hands, shared towels and bedding and by flies, it can lead to irreversible blindness, preventing adults from working and children from attending school and becoming a productive part of society.

While children are more susceptible, the blinding effects of repeated infection do not usually develop until adulthood. Women are up to four times as likely as men to be blinded due to their close contact with children.

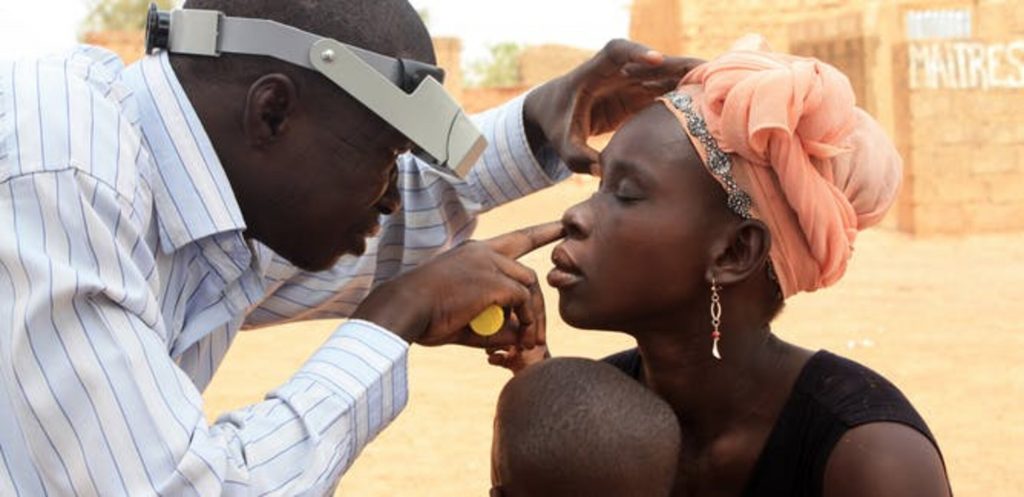

If caught early, trachoma can be treated with antibiotics, but if neglected, it advances to trachomatous trichiasis (TT) where the eyelashes move inwards, scraping the eye and causing extreme pain and scarring.

Once trichiasis sets in, surgery is the only solution before the damage becomes permanent, resulting in irreversible blindness.

Since a global campaign to eradicate the disease was launched in 1996, 10 countries including Nepal, Mexico, Cambodia, China, Ghana and Iran have been officially eradicated trachoma.

Nigeria has also made progress, reducing its at-risk population to 6 million in 2020 from 11 million in 2019.

WHO data shows Nigeria treated more than 9.3 million people with antibiotics and surgery in 2019, more than twice as many as in 2014.

Chukwuma Anyaike, director of the NTD elimination programme at Nigeria’s ministry of health, said the coronavirus pandemic had hit services, but everything was now “back to normal”.

“The COVID pandemic had a negative impact on NTD programming in Nigeria, but we were still able to make some deliverables and carry out interventions in the communities such as trachoma surgeries last year,” Anyaike said.

“Our main problem was a delay in funding from donors who initially felt it was not to safe to continue programs … I had to write them a letter to explain that we were working with all the necessary precautions.”

Despite the challenges, Anyaike said he was optimistic that Nigeria would eliminate trachoma.

MOTORBIKE EYE SURGEON

Organisations which support the government, such as Sightsavers and Helen Keller International, say they adapted to keep services running.

Even when Nigeria imposed a five-week lockdown, leaving trachoma patients unable to visit clinics, community health workers equipped with masks delivered antibiotics to their homes.

Sightsavers estimates that they were able to provide antibiotics to more than one million trachoma sufferers in Nigeria’s northwestern state of Jigawa alone last year.

While in northwestern Katsina state, eye surgeon Kabir Yahaya took to his motorcycle to provide post-surgery care to TT patients in their homes.

“When the lockdown happened, I realised that patients would not able to come to the clinic to have the sutures removed from their eyelids,” the 37-year-old TT surgeon told the Thomson Reuters Foundation by phone.

“So I decided to use my own personal motorbike to reach these patients and treat them at home. Many were in remote far off areas, but I managed to treat over 20 patients.”

NTD experts say diseases such as trachoma have been around for centuries, but have not been given the attention they deserve, largely because they afflict the poorest, often living in the remote under-developed rural areas.

In light of the coronavirus pandemic, some experts say there should be increased attention on disease like trachoma.

“I believe if NTDs like trachoma had the kind of focus that malaria or HIV had, we would have greater progress towards elimination,” said Philomena Orji, Nigeria country director for Helen Keller International which works on diseases of poverty.

“There is a reason they are called ‘neglected’. Even in terms of research, we have been using the same drugs for years. There doesn’t seem to be any new research into producing more efficacious medicine. They are neglected in every way.” (REUTERS)