Director of Robin’s Wish, a new documentary which tells the story of actor Robin Williams’ final days speaks to SkyNews

In the summer of 2012, Robin Williams wrote a note in the inside cover of his Twelve Steps book, just a short sentence detailing what he hoped might be his legacy. “I want to help people be less afraid.”

Two years later, he died by suicide at the age of 63; a tragic, traumatic end to a brilliant life.

Williams, known for his quick wit, his genius, his ability to always raise a smile, was no doubt incredibly afraid in his final days, unable to work out why his brilliant mind was, as he must have seen it, letting him down.

Despite outward appearances in his final on-screen role in Night Of The Museum: Secret Of The Tomb, on set he had been struggling to remember his lines. In private, the final months of his life had been consumed by anxiety, paranoia, panic attacks and insomnia, with no concrete explanation as to why.

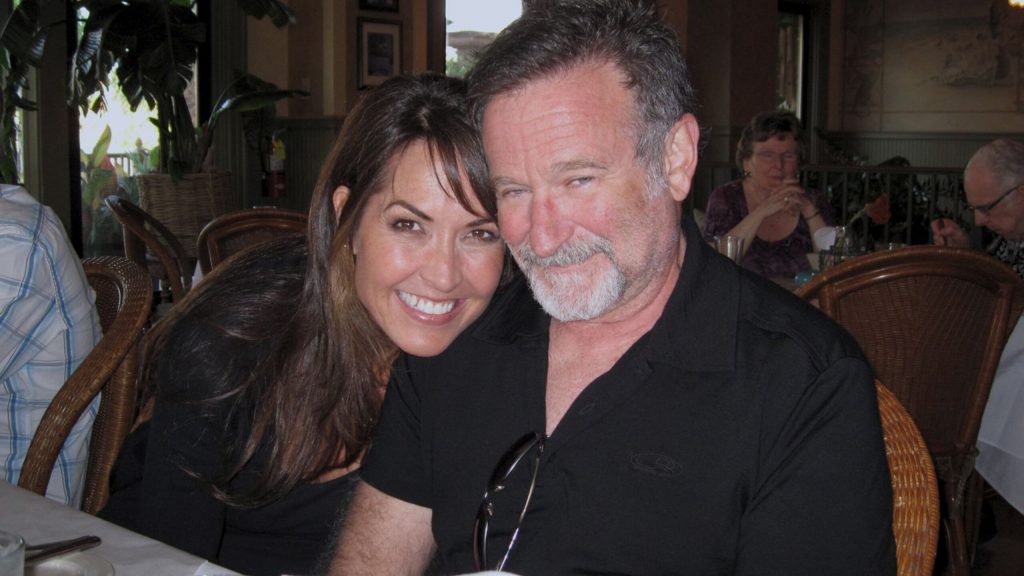

“Goodnight, my love,” he said to his wife, Susan Schneider Williams, on the evening of 10 August 2014. The next day, his home in a suburb of Marin County, San Francisco, became a shrine of mourning as news of his death made headlines around the world. “To the funniest man who ever lived,” summed up how he was viewed by the world in one of the many tributes left outside.

What Williams never found out was that he had been suffering from the neurological disease Lewy body dementia, a diagnosis that only came to his widow with a post-mortem following his death. Medical professionals said it was one of the worst cases they had ever seen.

Filmmaker Tylor Norwood, who was contacted by Schneider Williams to raise awareness of what really happened to her husband in his final days and years, now hopes to provide clarity and honour the actor’s memory in a new documentary film, Robin’s Wish.

It is important that the millions of people who loved him know the truth, he says.

“Robin Williams was in my life from like eight years old and the movies that he made followed me at points in my life that were important to me,” he says. “I think millions and millions of people had that experience with him. So when one of these [celebrities] pass in a way that’s jarring, that can be really disturbing.

“The reason this film needed to get made was because Robin deserved better, as a human who gave so much to us all, the idea that when he passed the real tragedy of his life is that he didn’t have an answer to what happened to him up until the end. He never got to know what this thing was.”

Many of the headlines, particularly in the US, that followed Williams’ death were filled with details of his depression, his previous struggles with addiction, speculation about financial problems, the documentary shows.

“The things that people grasp were just that – they were just grasping at things that didn’t have any weight to them or reality to them,” Norwood says. “So when the autopsy showed that he had Lewy body dementia to an extent that doctors really hadn’t seen before – and that’s to do with the fact that Robin was a genius and his brain was so good and so strong that it actually lasted much longer than theoretically you or I would have – that’s a very different story.”

There was speculation that “maybe he was back on drugs or maybe he’d lost all of his money… all these kind of guesses”, says Norwood. When the results of the postmortem were made public, they were reported, but coming several months after Williams’ death the director feels this important part of his story has been forgotten, that “the truth kind of got silenced because there just wasn’t any more attention for it”.

In Robin’s Wish, the star’s friends, family and colleagues speak about what he was like as a person, as well as the final years and days of his life. Director Shawn Levy opens up about Williams’ difficulties filming his final Night Of The Museum, saying that while he and the rest of the 200 or so cast and crew did not speak about it at the time, “it no longer feels loyal to be silent about it but maybe more loyal to share, without shame, without secrecy, that yeah, this guy was hurting, and he was going through something that he didn’t have a name for yet”.

In the documentary, Schneider Williams recalls her husband calling her while having a panic attack, and being paranoid and unable to sleep properly in his final months. “If we’d had the accurate diagnosis of Lewy body dementia that alone would have given him some peace,” she says.

She wanted the film to be made to raise awareness and maybe help others. Norwood says he also wants to remind people of exactly who Robin Williams was.

“Let’s remind people of all the light and beautiful things that he brought into the world. And then let’s say, oh, and by the way, everything you thought you knew about the end of his life was wrong. And that actually, no matter what narrative you clung to or got in those early days, the truth is who he was in the movies that you loved, the real guy was better than that.”

In Robin’s Wish, his neighbours tell of the star’s kindness and normality, talking of a wealthy, A-list famous man who chose to live in a quiet suburb rather than a gated LA community. It also shows the star visiting troops in Baghdad; something he did several times throughout his life. Despite his wildly different life, he identified with the soldiers and spoke to them about fear, something he said no one would guess he experienced himself. Williams always wanted to entertain and to help people, the documentary shows, whether that be children in his neighbourhood or soldiers in war zones.

“Everybody thought he must have been kind of this sad clown [after his death],” says Norwood. “He must have been really great in a movie but in his personal life, deeply troubled and upset…

“In reality, he was better than we all thought he was. If you loved him in the movies, he was better in real life.”

According to NHS UK, Lewy body dementia can cause hallucinations, confusion, fatigue and problems with understanding, memory and judgement. There is no cure, and the average survival time after diagnosis is similar to that of Alzheimer’s disease – around six to 12 years.

With Williams’ diagnosis coming after his death, the documentary does not give detail about how long he may have had the disease for. Schneider Williams says symptoms, which got progressively worse, were noticeable for about two years.

Dr Bruce Miller, director of the Memory and Aging Centre at the University of California San Francisco and a distinguished professor of neurology, is one of the medical experts interviewed in Robin’s Wish. “People who have great brains, who are incredibly brilliant, can tolerate degenerative disease better than someone who is average,” he says. “Robin Williams was a genius.”

Lewy body dementia is “a killer”, Dr Miller says in the film, a disease which is fast and progressive. “I’m looking at how Robin’s brain had been affected, I realised that this was about as devastating a form of Lewy body dementia that I had ever seen. Almost no area was left unaffected. It really amazed me that Robin could walk or move at all.”

Norwood and Schneider Williams have spent several years researching the condition. Norwood says it is impossible to say whether or not Williams would have taken his own life had he received a diagnosis while he was still alive, although there is no doubt the condition would have killed him eventually.

“There is no treatment for it, they can’t even slow it down,” the filmmaker says. “The one thing that having a diagnosis gives you, which is more valuable than almost anything else, is that it gives you an understanding that what’s happening to you is not your fault. That’s the real tragedy of Robin’s life, is he didn’t get to know that this wasn’t his fault.”

Dementia with Lewy bodies is caused by clumps of protein (the Lewy bodies) forming inside brain cells, says NHS UK. These abnormal deposits are also found in people with Parkinson’s disease, and build up in areas controlling functions such as thinking, visual perception and muscle movement, interfering with signals sent between brain cells. Despite the fact it receives substantially less publicity than other similar disorders, UK charity The Lewy Body Society says it is the second most common type of neurodegenerative dementia in older people after Alzheimer’s, accounting for approximately 15-20% of all people living with dementia.

Although he did not know it, Williams was one of about 1.4 million people living with the condition in the US. Before he died, the actor was seeing a therapist four or five times a week, Norwood says, trying yoga, hoping “he could think his way out of this, not understanding that it was a physical thing that was happening and it wasn’t mental”.

He continues: “The one thing I learned about him through the making of this film is that he was resilient, he was someone who, whether it was with tragedies that happened in his life, whether it was with addiction, he always found a way to rise to the occasion and be better and work harder and get through it so he could be present for all of us.”

After the release of Robin’s Wish in the US in September, it topped the film chart and remained the number one documentary for a month, which “speaks to Robin’s legacy”, says Norwood.

What he hopes fans will take from the film is the desire to see Williams at his effervescent best once again.

“My dream is that people will watch this movie and as the credits start rolling, they’ll go, I want to watch Good Will Hunting or I want to watch Dead Poets Society or I want to watch Aladdin.”

Robin’s Wish tells the powerful true story of actor/comedian Robin Williams’ final days. For the first time, Robin’s fight against a deadly neurodegenerative disorder, known as Lewy Body Dementia, is shown in stunning detail

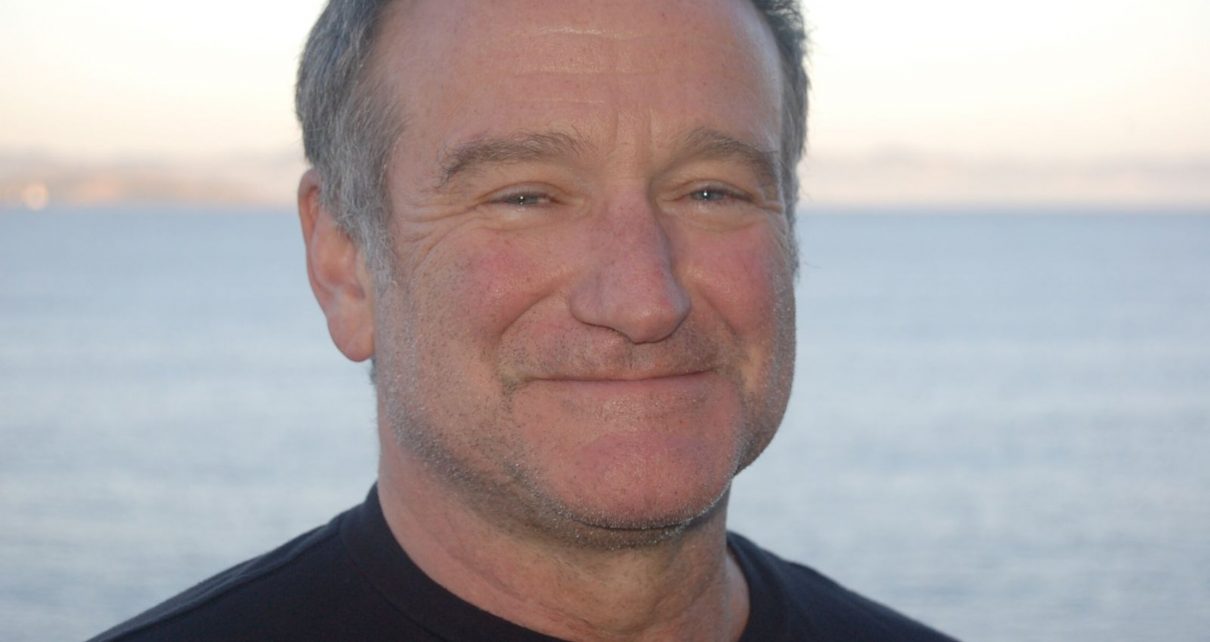

Image:

In the years before his death, Williams said he hoped this would be his legacy

Doing justice to the star’s story with the help of his closest friends and family came with a huge sense of responsibility “to do right by all of them”, Norwood says. There were many lovely stories about the star that he didn’t have time to include.

“Most of the time was them talking about how lovely he was, like how on set he would just do like improv for 45 minutes or how he would donate his time or how his friends in the neighbourhood were like, he’d be out in front of our house with chalk, drawing with the kids on the pavement, and those were things that couldn’t all make it into the movie.

“It was powerful to me to see how much of a difference he made in these people’s lives across the board and how much he really touched them.”

Because whether you knew Williams best as an alien, a genie, or Peter Pan; as a desperate father turned nanny in drag, or an English teacher urging students to make their lives extraordinary; as an Oscar winner, a stand-up comedian – or, for a lucky few, simply Robin Williams the man – he was someone who brought joy to millions. And no doubt helped us all be a little less afraid.

Robin’s Wish is out on digital and on demand in the UK from Monday, 4 January (SkyNews)